Susannah Mushatt Jones became the world's oldest person on Wednesday.

She has loved bacon for more than a century. Jones is 115 years old,

and the meat is the first thing to disappear from her plate every

morning. The eggs go next.

Last month, we arrived five minutes late for breakfast in Jones'

home, a sunbathed one-bedroom in the Vandalia Houses, a public-housing

facility for seniors in the Canarsie neighborhood on the southern edge

of Brooklyn, New York. She'd already dispensed with the bacon and was

tackling the grits. Jones is blind, and partially deaf, but with steady,

fervent hands, she searched her plate for morsels and shoveled them

into her mouth.

The routine is the same each day for Jones. When she finishes the

grits, she unwraps five sticks of Doublemint gum and tosses the papers

on the floor beside her slippers. She likes to chew them all at once

because, as her caretaker explained, "they're making them so flimsy

now." The oversize armchair engulfs her as she leans back to sleep.

As the oldest person in the world, Jones is one of two verified people remaining who were born in the 1800s. She's one of about 40 supercentenarians, or people who lived past their 110th birthday.

Her age has earned her something of a celebrity status. When we

entered her building, other residents spotted our cameras and

immediately asked if we were there to see Jones, or "Miss Susie" as

she's known among family and friends. A newspaper clipping about Jones

hangs in the lobby, and her room is decorated with cards she's received

from notable well-wishers over the years, including President Barack

Obama (whom she voted for in 2008), former New York City Mayor Michael

Bloomberg, and children from local schools.

While Jones' feats of longevity aren't entirely unparalleled (a

Frenchwoman once lived to be 122, the longest confirmed human lifespan

on record), her nearly perfect bill of health has amazed doctors and

family for more than a decade. We met with Jones and her niece, Lois

Judge, to find out what it takes to be a supercentenarian.

A long way from Lowndes County

Jones doesn't look a day over 100. The Lowndes County, Alabama,

native has smooth, soft skin, like peach fuzz. Patches of light brown

hair cover her head, while whiskers pepper her chin. Her frame is small —

maybe 5 foot, 90 pounds — a far cry from the sturdy woman she was in

her youth. Still, the most prominent giveaway of Jones' age is a cloudy

left eye. Glaucoma took her sight 15 years ago.

But the moment Cecily Freser, her live-in caretaker of more than 12

years, clears the breakfast plate from her lap, Jones nosedives into a

pillow resting on the recliner's arm. She sleeps most of the day, with

the radio or a daytime-TV game show playing in the background, though

she probably can't hear it. These days, Jones mainly responds to the

voices of her family members and friends.

"Sometimes she'll ask a question," Freser said, "and sometimes she'll

laugh to herself. She'll say, 'I was thinking about something someone

did long, long ago."

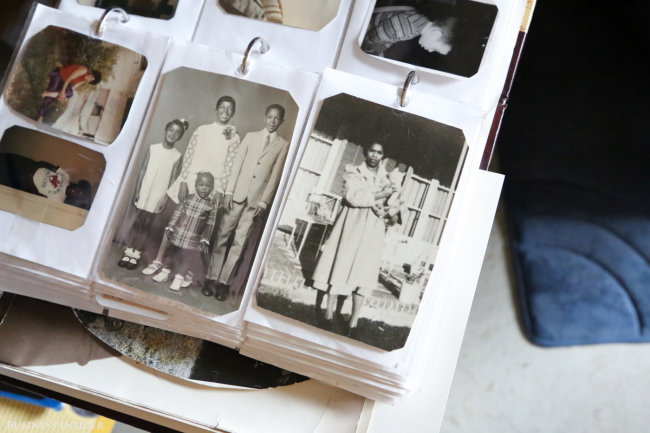

Born July 6, 1899, Jones grew up the third oldest of 11 children in

the Alabama countryside, about an hour southwest of Montgomery. Her

parents worked as sharecroppers. After graduating from high school in

1922 (she's kept the class roster over the years), she was accepted to

the Tuskegee Institute's teaching program. However, her family couldn't

afford to send her. A year later, she hopped a train to New York City.

Jones found work as a nanny for wealthy white families, and she

traveled the country with them, from New Jersey, Vermont, California,

and Mexico to Westchester, New York. Some of the children she helped

raise have stayed in touch with her family over the years and visited

her at the apartment in Brooklyn. Jones never had children of her own,

though she was married briefly to a man named Henry Jones, and took

great pride in the kin she cared for professionally. She roomed with the

families, and on days off, stayed with friends in an apartment at 145th

Street in Harlem, New York.

Throughout her life, Jones lived simply: no parties, smoking, or

alcohol. Her greatest indulgence was lace lingerie from Bloomingdale's,

with which she reportedly startled her doctors when she sported it during an EKG appointment years ago.

Jones had no trouble spending money on her family, however. At

Christmas, she gifted pill boxes of pennies, nickels, dimes, and

quarters to the young ones. She loved to bake cakes for company. And

Jones used her salary to send her nieces to college and to provide

scholarships for other Alabama students, so they would not be prevented

from attending college as she was.

Judge, her niece, still has the cashmere sweater adorned with pearls

that Jones sent her while she was away at school. Dressing well provided

a crucial source of pride for Jones, who grew up as an African-American

woman in the segregated South. She once returned to Alabama for the

funeral of a family member. When she stepped off the platform in

Calhoun, a predominantly white area, the bystanders gawked at her

outfit: a jacket, hat, gloves, and bag on her arm.

"They said, 'Who is this important person getting off the train?' She

felt so proud," Judge said, having heard her aunt tell the story over

and over. "But of course, who was there to pick her up but someone with a

wagon and a mule?"

In 1965, Jones joined the family at Mushatt Farms in Alabama, where

they raised cattle and horses, and stayed 10 years. She loved the

countryside and would have gladly lived out her 50-plus-year retirement

there. But as more relatives migrated north, her growing dependency on

them forced her to follow.

One in 7 million

Jones represents a very rare slice of the demographic pie. Supercentenarians occur at a rate of about one in 7 million people. In the US, roughly a dozen of every 4,500 centenarians, or people who reach the age of 100, will live past their 110th birthday.

A surprising majority, like Jones, are in great shape. According to the Boston School of Medicine-New England Centenarian Study, a leading center for longevity research, 69%

of supercentenarians show no signs of age-related diseases, such as

cancer, cardiovascular disease, dementia, and stroke, at age 100 or

later. Another study found 41%

of supercentenarians require minimal or no assistance in activities of

daily life, such as feeding, bathing, and getting in and out of bed.

Jones' daily regimen is simple. Every morning with a glass of water

and cranberry juice, she takes a multivitamin and a blood-pressure

medication. She sees the doctor just four times a year for

"maintenance," Judge said. Along with chewing gum and her breakfasts,

Judge said Jones' diet largely consists of fruits. She never complains

of pain. To the bewilderment of her physicians and family members, Jones

even appears to be "reverse aging." Over the last four years, her hair

changed from gray to brown and softened. When she was 96, she grew a

tooth — not a wisdom tooth, not an impacted tooth, but a new tooth — in

her lower jaw. She's a medical marvel.

For decades, researchers have engaged in a modern-day space race to

identify the common thread among supercentenarians that allows them to

live so healthily, so long. Jones checks off a few boxes.

The genetic jackpot for long-lasting life

Jones is a woman, and that counts for something. About 90% of

supercentenarians are female. The New England Centenarian Study suggests

that women may biologically fare better than men when age-related diseases manifest, meaning they hold on longer despite illness.

In her heyday, she never abused alcohol or drugs. Even coffee was too strong for her tastes.

Most important, Jones has good genes. Her niece Judge told us that,

according to the US Census, Jones' grandmother lived to be 117.

The research is inconclusive, but it suggests that supercentenarians

have ingrained protective mechanisms — basically a complicated web of

genes — that help them avoid age-related diseases and delay cognitive

and functional decline.

George Church of Harvard Medical School explained it best in an interview with io9's George Dvorsky:

"To appreciate why it's so extremely rare

to live to 107 and beyond you need to think about it this way. It may

take several genes to help protect a person from various forms of

cancer. You can have all of those genes, but still die early of

cardiovascular disease. If you have genes that protect you from the many

forms of CVD, you may nevertheless still die early from cancer,

neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, and so on. So a person likely needs numerous protective genes in every major category of disease risk, in order to sidestep these typical longevity landmines."

As researchers scramble to pinpoint the winning DNA combination, Jones sticks with her routine.

Strength in family

According to Judge, Jones partially attributed her longevity to

family. She never had children or a husband of her own, but she still

had a large family around her to provide comfort, contact, and a support

system.

For the past 30 years, Jones has lived in her apartment in the

Vandalia Houses. Her nieces and nephews visit every Sunday, and she will

call out any one of them who misses a week. Though she can't see them,

she recognizes their voices and the ways they interact with her; one

likes to tap her on the head, for instance. Judge knows it's possible

one of them will live to be 115 years old, although she hopes it's not

her.

"I don't think I would have the support that she has," Judge said. "She's had good people with her."

Still, the apartment doesn't feel like home to Jones. "She wants to

go back to Alabama, that's her main thing [these days]," Judge said,

quoting her aunt's refrain, "'I want to go home, I want to go home.'"

They try to remind her that the family no longer lives at the farm,

with seven Mushatts residing nearby. Brooklyn is her home now. Jones

will often reply, "'No, this is not what you call home."

Then she goes back to sleep, where her family likes to think she returns to Alabama.